While breezing through pictures stored on my phone earlier this morning, I came across this picture of Dad.

I remember snapping the photo like it was yesterday.

Dad was waiting to be discharged from St. Mary’s cardiology floor, a place we visited many, many times during the nine months that I spent with him following his diagnosis for Congestive Heart Failure. With the help of my BFF Tanya, I’d taken him to the ER the night before this picture was taken, and he’d been kept overnight to receive fluids and a round of Dobutamine, a miracle drug that kept Dad’s heart pumping long after it might have shut down.

Dad grew frustrated by the “Hail Mary” trips to the ER, which occurred 1-2 times a week as he neared the end of his life. But diligent daughter/caregiver than I am, I was on top of every sign of distress I observed.

Extreme confusion, signaling a urinary infection.

Swelling ankles–more than usual–suggesting that his fluid intake was out-of-whack.

Severe unsteadiness, an indication that his medications might require readjusting.

“Those doctors keep saying the same thing,” he’d tell me following each trip to St. Mary’s ER. “Why do you come here? We can’t do anything more for you.”

Harsh as those comments might sound, they were spoken in the gentlest tones.

Dad would joke with the ER docs that he’d shown up to see whether there had been any new medical breakthroughs, something that might fix his woes. Dad had great faith in medicine and science and trusted that the best and the brightest would continue to figure out life’s mysteries, at least the ones we mere mortals are supposed to understand. His decision to donate his body to Loyola Medical School was an indication of his trust in doctors and the importance of supporting their steadfast study of human specimens.

Plus, as he frequently reminded me, “you get a discount on the embalming and transport of the body if you take the donation route.” Sigh.

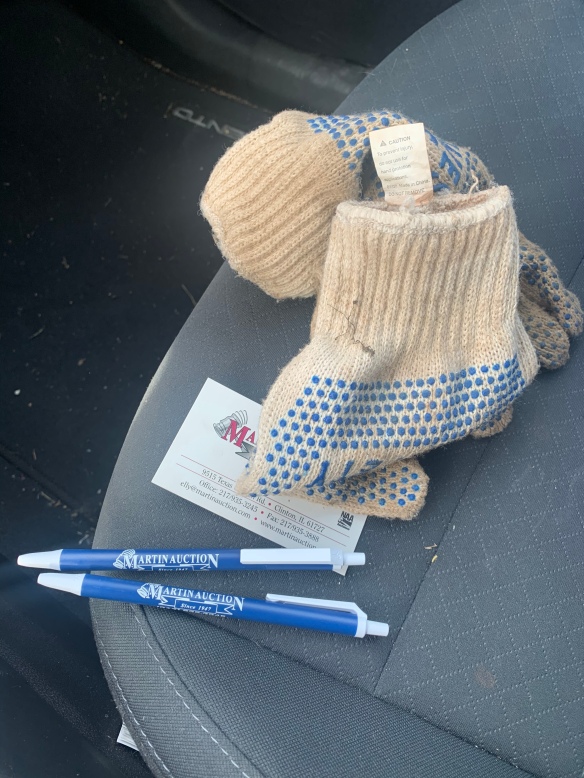

When I look at this photo, taken in early November 2017, I see two of Dad’s most memorable traits.

- He was ready to go, to leave this world at any time. Every Sunday since he was a child, he prayed at the local Catholic church–long after his knees and hips prevented him from kneeling on a pew–asking the Lord to forgive him his transgressions and bless him and those he loved. Dad believed that when God comes knocking, you’d better be ready to answer the door. Don’t wait until the last minute to get your house in order.

- He was ready to head out to the fields, one more time or however many times he had left. On the way home from the hospital that day, like all the other return trips from St. Mary’s, I’m certain we drove by the fields to see what crops remained to be harvested.